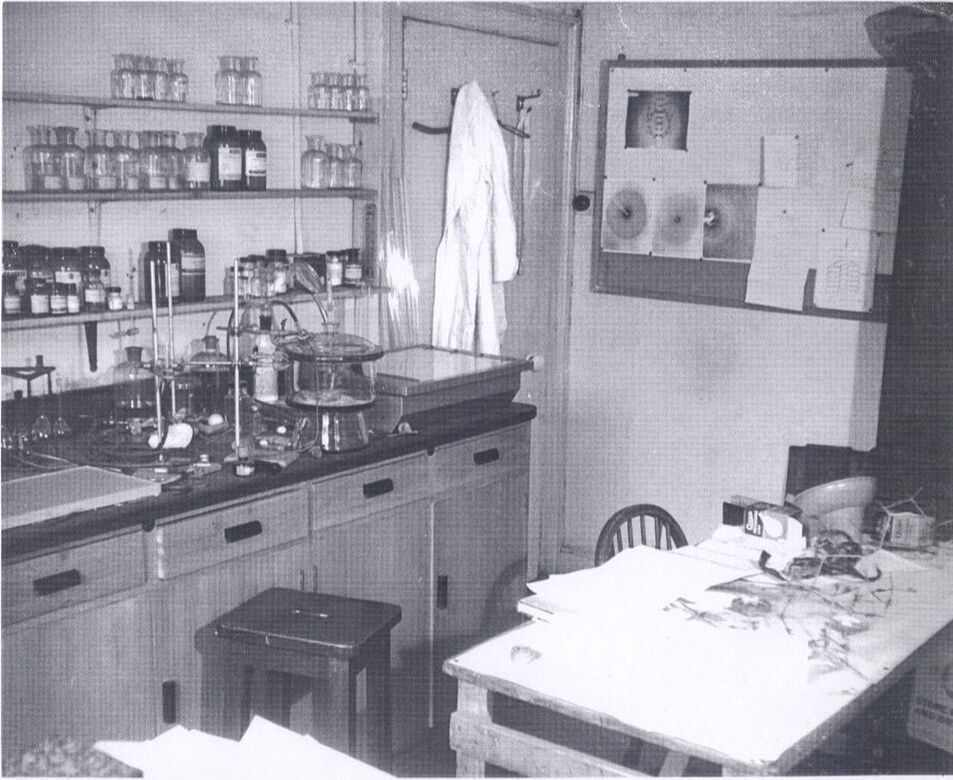

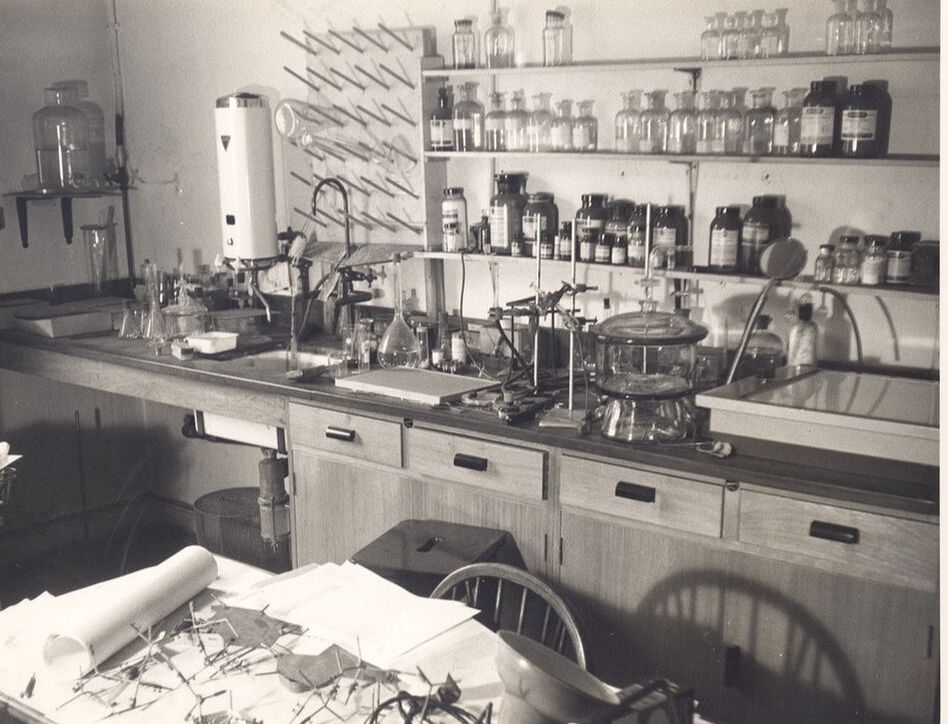

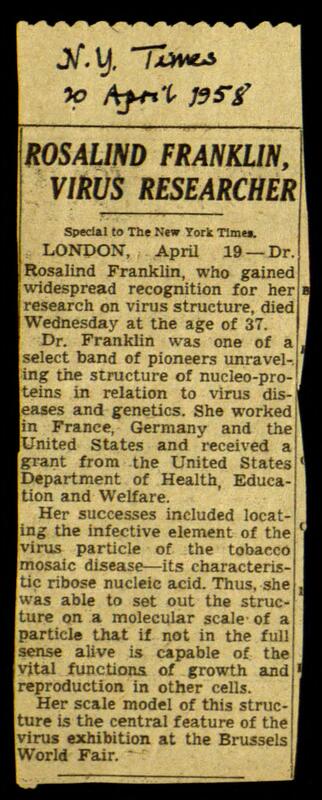

It was during a trip to America to look for a research grant from the NIH, in the summer of 1956, when Franklin began to experience sharp abdominal pain and swelling. On her return to London in September of that year, her doctor suspected she had ovarian cancer. It was confirmed with a surgery. The next month she had another surgery. She finally returned to work in the first month of the new year. With her illness, the placement of her lab went from inconvenient to problematic and exhausting. Throughout 1957, Franklin underwent many treatments and surgeries, going back to work as much as she could. At Birkbeck, Franklin and her team produced a good number of journal articles, including "The Helical Arrangement of the Protein Sub-Units in Tobacco Mosaic Virus", "The Structure of Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus: X-Ray Diffraction Studies", "On the Structure of Some Ribonucleoprotein Particles", "Order-Disorder Transitions in Structures Containing Helical Molecules", "The Structure of Viruses as Determined by X-Ray Diffraction", and "The Crystal Structure of Tipula Iridescent Virus as Determined by Bragg Reflection of Visible Light". Franklin made numerous contributions to the study of plant viruses while at Birkbeck, and even began planning a project studying the polio virus. April, 1958

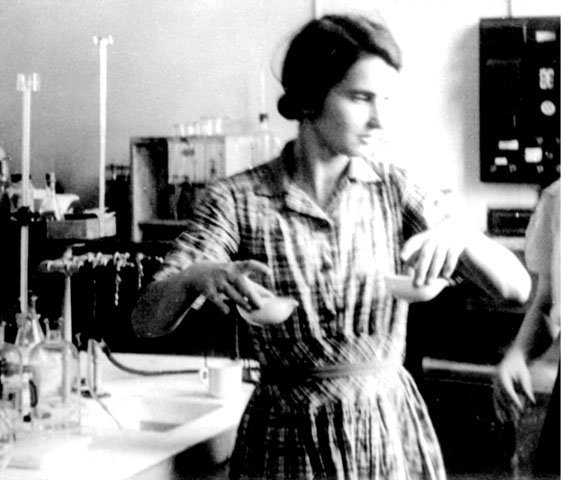

Legacy Throughout her life, Rosalind Franklin made so many contributions to science. She started with using x-ray diffraction for coal research and then turned that technique to study biological molecules. She was instrumental in discovering the structure of DNA, and made great contributions to studying plant viruses. Her work with coal earlier on was groundbreaking. Franklin died before she was 38. I wonder what she would have done if she lived a longer life. I wonder how she would have wanted to be remembered. Some people see her as a victim -- a martyr -- of sexism in science. Others see her as an amazing scientist who accomplished so much in her short life. Others don't remember her at all. I wonder what she would have wanted. How would she have wanted her story told? How would she have wanted the world to remember what she did?

7 Comments

In 1951, Rosalind Franklin went back to London to work in J. T. Randall's biophysics program at King's College. It was very different from Paris. "London in the 1950s seemed to Rosalind to be sunk in pessimism, while Paris, recovering from the horrors of occupation, was forward-looking and full of optimism," writes Jennifer Glynn in her memoir My Sister Rosalind Franklin. The work environment as well was in high contrast to her last job. Sexism was built deeply into the work environment. It was very unwelcoming in contrast to Mering's lab in Paris, as Glynn describes: "There were certainly a surprising number of women scientists at King's, but they were not allowed in the men's common room, where there was lunch and coffee and contact with colleagues--an insulting situation, even if not unusual in England at the time; it hit Rosalind particularly badly after the freedom and friendliness of the lab in the Quai Henri IV. And the immediate hostility between Rosalind and her colleague Maurice Wilkins has become notorious." This was King's College in the 1950s. This was when Franklin stepped into the famous and messy race for the structure of DNA. Franklin didn't intend to work on DNA when she came to King's College. "Franklin's fellowship proposal called for her to work on x-ray diffraction studies of proteins in solution. However, there was a shift in research priorities after Maurice Wilkins, the assistant director of Randall's lab, began working with an unusually pure sample of DNA obtained from Rudolf Signer. Excited about the possibilities, Wilkins suggested to Randall that Franklin's expertise might be better applied to this promising DNA research. Randall agreed; he wrote to Franklin in November 1950, explaining the change of plan, and stated that she and graduate student Raymond Gosling would be the only staff doing crystallographic studies of DNA. Randall did not mention Wilkins' serious interest in DNA, nor did he tell Wilkins the details of the letter. These omissions soon generated misunderstandings between Wilkins and Franklin--Franklin assumed that the x-ray diffraction studies of DNA would be her project alone; Wilkins assumed that she was joining the loosely organized research team ('Randall's Circus') at the biophysics lab, as the expert on crystallography." (The Rosalind Franklin Papers, NIH) These misconceptions heightened tensions between Franklin and Wilkins, which weren't helped by a personality conflict between the two.

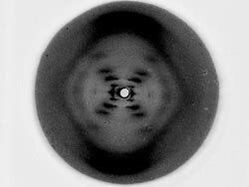

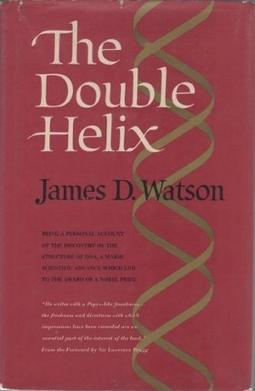

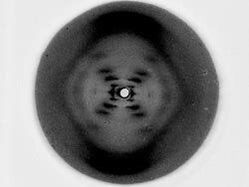

I suspect that in the beginning Maurice hoped that Rosy would calm down. Yet mere inspection suggested that she would not easily bend. By choice she did not emphasize her feminine qualities. Though her features were strong, she was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even mild interest in clothes. This she did not. There was never lipstick to contrast with her straight black hair, while at the age of thirty-one her dresses showed all the imagination of English blue-stocking adolescents. So it was quite easy to imagine her the product of an unsatisfied mother who unduly stressed the desirability of professional careers that could save bright girls from marriages to dull men. But this was not the case. Her dedicated, austere life could not be thus explained--she was the daughter of a solidly comfortable, erudite banking family. There's no question why Franklin was unhappy there. It was in this environment that Franklin worked studying DNA with x-ray crystallography. It was here that Franklin and Gosling produced the famous Photograph 51 of DNA. Wilkins showed this photo to Crick and Watson, without Franklin's knowledge or permission. Crick and Watson used this photo as crucial proof in their designs for a model of DNA. They never gave her credit for it in their journal article. The sad thing is is that Franklin never knew they took her work. We'll never get to know what she would have felt about it. Franklin died before Crick, Watson, and Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel prize in medicine. Had she been alive, she might have gotten the credit she deserved.

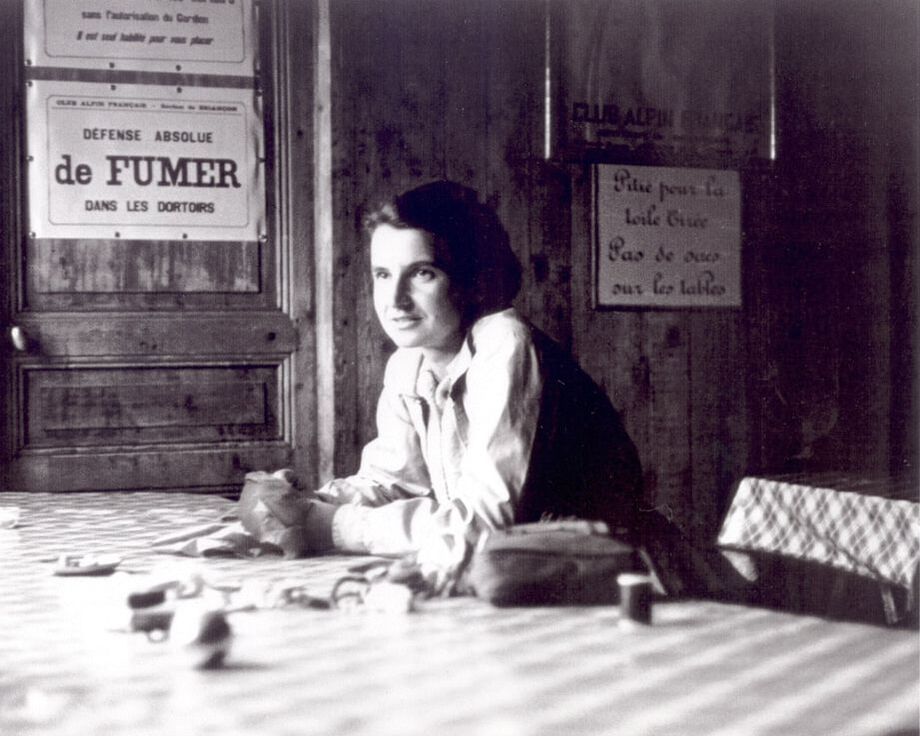

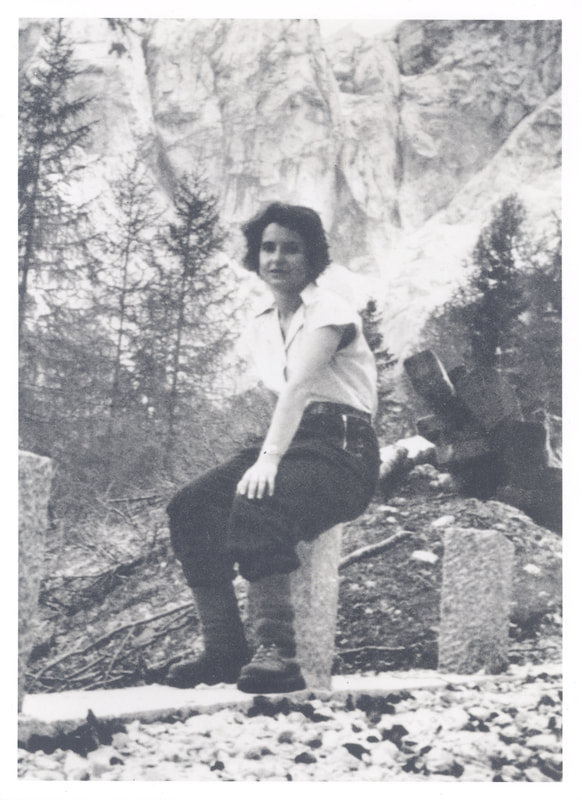

Personal Life: Influences and Relationships1945. WWII had ended, and Franklin, in June of that year, went back to Nenwham to write her Ph.D. thesis from her work at BCURA. Since the war was over, Franklin happily took up international travel again. During the war she had gone on mountain climbing trips and the like, but only in Britain. Now she was glad to be able to travel elsewhere as well, such as one hiking trip to the French Alps she went on with her good friend Jean Kerslake. "If ever you hear of anybody anxious for the services of a physical chemist who knows very little about physical chemistry but a lot about the holes in coal, please let me know." This was from a letter Franklin wrote to her friend Adrienne Weill. After her trip in France, she was ready for a change of pace with her work, especially hoping for a job in France. Franklin didn't really expect to find one, but Weill was in fact able to help. "Adrienne once more became [Franklin's] saviour, telling her that at the conference on carbon that was to take place at the Royal Institution that autumn there would be two French scientists, Marcel Mathieu and Jacques Mering, both friends of hers, who would like to meet Rosalind and might be able to help her. Rosalind presented a paper at the conference, asked intelligent questions, and showed the visiting Frenchmen round London. They were impressed," catalogues Jenifer Glynn in her memoir of her sister.

Jenifer Gynn writes of Luzzati and Franklin's friendship: "Luzzati shared Rosalind's taste for heated discussion and argument--Anne Sayre records a colleague saying, 'When Vittorio and Rosalind were together, it was hammer and tongs and quite exhausting'. And Vittorio and his wife Denise also shared her taste for the countryside and energetic holidays. Rosalind joined them for their great bicycle tour in Tuscany in 1950--'unforgettable' as Vittorio Luzzati wrote--in a countryside as yet untouched by tourists. It is still a good memory for him.... Whenever possible they would escape to the Alps, too, or all go off to the countryside at weekends."

Franklin also developed a relationship with her supervisor, Jacques Mering. Glynn writes that Franklin thought highly of him and Mering was impressed with her abilities. Franklin formed these good friendships and many others in Paris. Key word being friendships. People often tried to put more into them then there was. Glynn puts it well: "[Franklin] was twenty-six when she arrived [in Paris], and single. Paris has always had a reputation as a romantic city, so there have been various suggestions about her possible romantic life there--but all of them are wrong; her happiness came simply from a love of the place, from friendships, and from fulfilment in her work." People have a tendency to ship famous and historic figures, particularly the female ones. The whole thing is absurd. It is frustrating that people don't understand that a woman doesn't necessarily have to have an active romance life. First, they decided on Luzzati. Glynn puts the whole mess perfectly: "The BBC TV Horizon programme implied a relationship with Vittorio Luzzati; in fact, although they were colleagues and always remained excellent friends, they were certainly no more than that. Since there was no future there, Jacques Mering, Rosalind's supervisor, was later suggested as a candidate; he, as it happens, already had a wife and a mistress. Rosalind admired Mering as a scientists, and she must have felt a pang of nostalgia when he rang her and came to see her later in her illness. He reportedly wept after seeing her--as he might have done after seeing any young talented pupil close to death. It is wrong to read any more than that into their relationship." Research Work: Coals and CarbonIn Paris, Franklin continued on an extension of her research conducted at BCURA. She wanted to look even closer at the microstructures of coals. For this, she needed X-ray diffraction! She was in the right place for this now, with Mering to teach her as needed. Franklin's research in Paris yielded even more published journal articles authored by her. In her time in Paris, she became very skilled at X-ray crystallography, which she would later turn towards studying biological structures. She also grew in prestige as a scientists. She is remembered in having great contributions to the field of coal and carbon research.

* Full citation: Periodical. Franklin, Rosalind. "On the Structure of Carbon." The Journal de Chimie Physique et de Physico-Chimie Biologique 47, (1950): 573-575. Article. 3 Images.. The Journal de Chimie Physique et de Physico-Chimie Biologique ** Full citation: Periodical. Franklin, Rosalind. "Crystallite Growth in Graphitizing and Non-Graphitizing Carbons." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 209, (1951): 196-218. Article. 25 Images.. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London

Franklin and Bangham were looking at how the thermal expansion of charcoal and coal was affected by the amount of methanol was saturated in the coal or charcoal. The expansion of charcoals with the absorbed films of alcohols is harder to measure since it's very complex: at first it expands much faster than dry charcoal, but then it shrinks before expanding again due to the moisture evaporating from it. Franklin and Bangham devised a method to measure this more accurately by a method of preheating the coals to high temperatures. After this paper was published, Franklin published her own journal article in 1948 ("A Study of of The Fine Structures Of Carbonaceous Solids by Measurements of True and Apparent Densities: Part I. Coals," 1948, shown below) which detailed her experiments in apparent density of coals at BCURA.

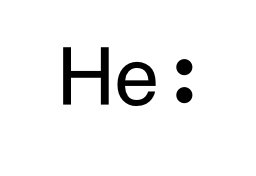

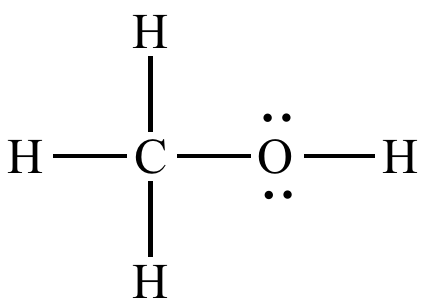

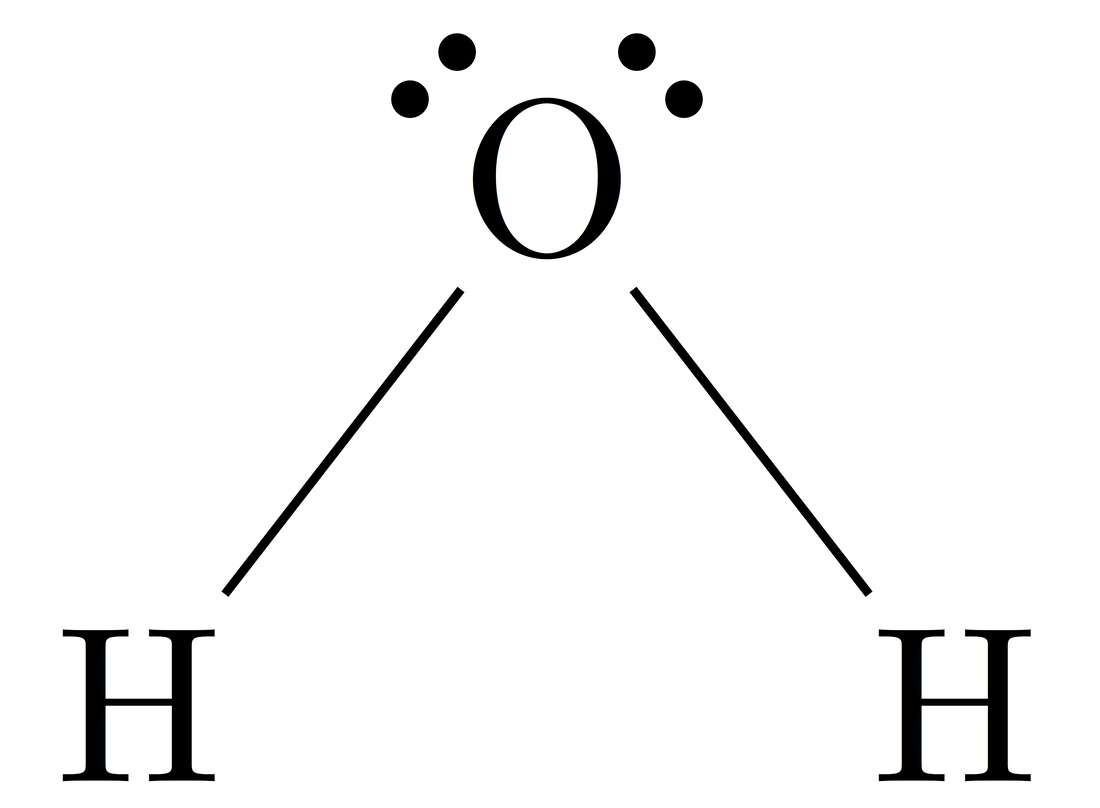

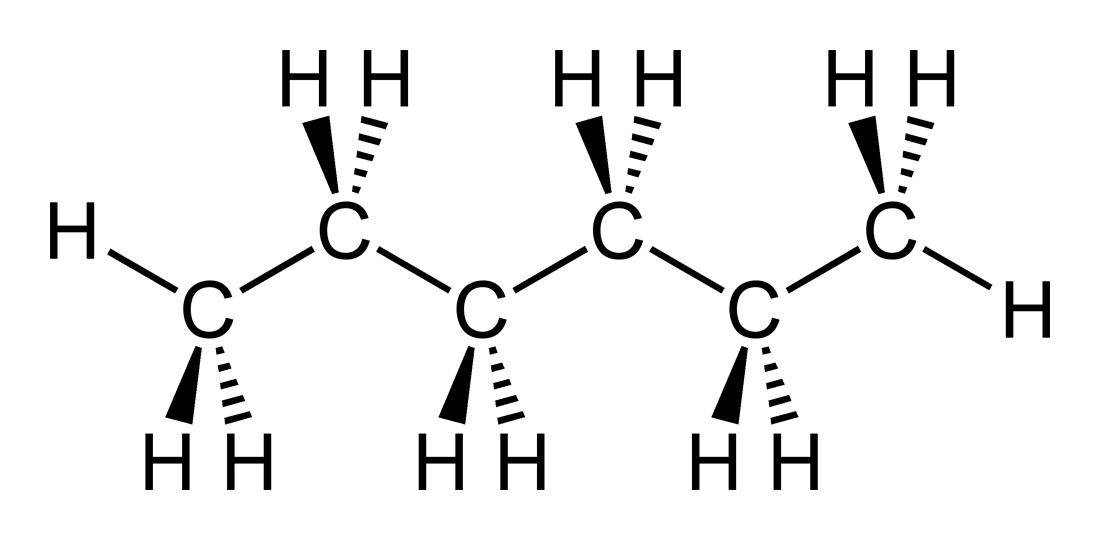

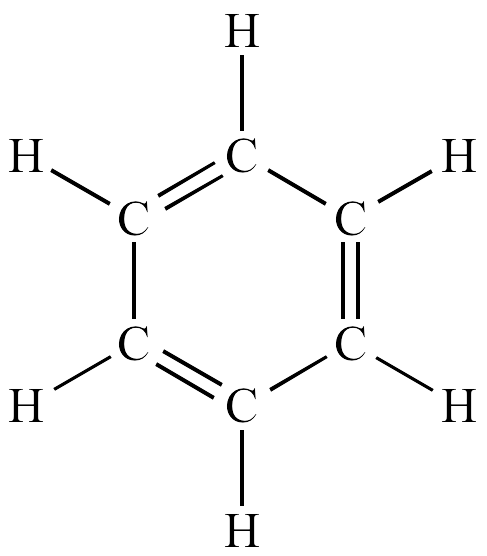

Smaller molecules (helium is a great) give apparent densities closer to the true densities of materials. No matter how small of a molecule you use, however, it will not fill completely closed off holes in the material. The fluids Franklin used in her experiment were helium gas, methanol, water, n-Hexane, and benzene. The chemical structures of these gasses and liquids are shown in the above order below. (Note: If you are not familiar with Lewis Structure notation, in short, the two dots represent unbonded electrons and the lines represent bonds. (The triangle shapes in the structure for n-Hexane indicate 3D shape.)) Image credits, from left to right: 1. www.chemistrylearner.com/helium.html, 2. web.chem.ucla.edu/~harding/IGOC/M/methanol.html, 3. socratic.org/questions/5495372e581e2a1c2d5edb9f, 4. socratic.org/questions/595fa291b72cff185f0768e2, 5. arstechnica.com/science/2017/02/researchers-individually-craft-molecules-of-a-reactive-triangular-chemical/ The second part of Franklin's article, "A Study of of The Fine Structures Of Carbonaceous Solids by Measurements of True and Apparent Densities: Part II. Carbonized Coals" (shown below) was published in 1949.

* Full citation: Periodical. Bangham, D. H., and Rosalind Franklin. "Thermal Expansion of Coals and Carbonised Coals." Transactions of the Faraday Society 48, (1946): 289-295. Article. 7 Images.. Transactions of the Faraday Society

** Full citation: Periodical. Franklin, Rosalind. "A Study of the Fine Structure of Carbonaceous Solids by Measurements of True and Apparent Densities: Part I. Coals." Transactions of the Faraday Society 45, (1949): 274-286. Article. 13 Images.. Transactions of the Faraday Society *** Full citation: Periodical. Franklin, Rosalind. "A Study of the Fine Structure of Carbonaceous Solids by Measurements of True and Apparent Densities: Part II. -- Carbonized Coals." Transactions of the Faraday Society 45, (1949): 668-682. Article. 15 Images.. Transactions of the Faraday Society

Franklin and her cousin volunteered as air-raid wardens during this time. Their jobs involved making sure the 'blackouts' were observed adequately, serving two-hour shifts at the wardens' post, and going out in emergency situations. These were quite trying experiences for Franklin, as Jenifer Glynn, Franklin's sister, explained in her memoir: "Crossing Putney Common for her duties, at night during air raids, was a worse ordeal for Rosalind that we realized at the time--sometimes in the distress of her last illness it haunted her dreams." Franklin grew in prestige during her time working for BCURA. She worked on her research there for four years (ending in 1946). BCURA did research in coal, relating to the war. Franklin's studies, in particular, focused on tiny pores in coal. Franklin's research was a huge contribution to the study of coals. For example, in a quote Glynn included in her memoir, Peter Harris wrote in reference to Franklin's work: "This was probably the first demonstration of molecular sieve behaviour in any carbon. Today [2001], carbon molecular sieves are of great value in industry where, among other things, they are used to separate nitrogen from oxygen in air."* Franklin's research at BCURA involving the properties of coal, which I will expand more upon in the next post, became her dissertation for her Ph.D. (which she received from Cambridge in 1945) as well as several published scientific journal articles. * P. J. F. Harris (2001), 'Rosalind Franklin's work on coal, carbon and graphite', Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 26, 204-10

Rosalind Franklin got her Bachelor's degree in Physical Chemistry in 1941. She didn't leave Cambridge until 1942, though. She had received a research grant and a scholarship for another year at Cambridge as a research student. She worked under Ronald Norrish who was the Professor of Physical Chemistry in the area of research on the kinetics of polymerization reactions. While he was an impressive scientist (in fact, he would go on to win a Nobel in 1967), he was often criticized for being a stubborn and inflexible professor to his students, especially the women. Franklin was frustrated with the work Norrish assigned her. She felt it didn't help the war effort and wasn't worth her time. She also disagreed with some of his conclusions. She was frustrated with his inattentiveness to her ideas. She was usually very direct and honest about her point of view, so she voiced these concerns to him. This, of course, often didn't bode well. Their two conflicting personalities and differing ideas often led to conflicts in their relationship. Franklin complained about him some of her letters. In a letter addressed to her family, written in December, she voiced her frustrations: I'm only just beginning to realise how well justified his bad reputation is. Well I've now got thoroughly on the wrong side of him, and almost reached a deadlock. He's the sort of person who likes you all right as long as you say yes to everything he says and agree with all his mis-statements, and I always refuse to do that. He tells me I mustn't take any step without asking him and has now run out of ideas and tells me to go back and try the first method again (after I proved three months ago that it didn't work). I refused, and we parted angry.... She cut her time as a research student at Cambridge short. While she could have stayed up to two or three years working there, she found the work not worthwhile enough for her and left in 1942. While she disliked her work during her time researching at Cambridge, she did enjoy her personal life. She lived alone -- and quite liked it, according to her letters home -- and enjoyed her independence. She liked reading, having visits from friends and family, and going to theaters and art exhibits according to her sister. When her college friends left Cambridge, though, she felt lonelier. In one melancholy letter home, she wrote: I live alone, and most of my friends have gone--all the friends that remain go down for good this month. I am intensely bored with my work, I despise my professor. I dislike the men who work in my lab, and they resent and generally ignore my presence. Franklin's friend Adrienne Weill came along and pulled her out of her loneliness. Adrienne Weill was a French Jewish refugee and scientist who came to Cambridge during Franklin's time at Newnham. She developed into Franklin's role model and friend. In May, Weill invited Franklin to stay at her house for foreign students. While at first hesitant, Franklin accepted and moved in in June. Also in June, the Ministry of Labour announced that women research students were now able to be 'drafted' into war related work. While her work at Cambridge was stable and could be considered war work, she decided to take a chance and look for different research work, more directly related to the war effort. This is how we come to the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA). BCURA offered Rosalind Franklin an opportunity to gain her Ph.D. while working for them. Franklin also disliked her research experience at Cambridge, so the benefits of switching to work at BCURA were obvious. However, Franklin was hesitant. Particularly, she wasn't too happy about the isolation of the lab, which would be several miles away from town. This would be a contrast to her current life living in Weill's international house. She also may have been disappointed in having to stop teaching. In the end she accepted BCURA's offer. And so, during the year 1942, she arrived at Kingston-on-Thames, right outside London, to work in coal research in the position of Assistant Research Officer in BCURA.

Rosalind Franklin grew a lot during her time at school. She became very vocal and serious about politics, as her sister describes in her memoir: "Her very full and frequent letters show her gradually maturing from her schoolgirl outlook, when she tended to echo her parents' beliefs (except in religion, which she had already firmly rejected), to her own outspoken left-wing independence." She would often write about politics in her letters while she was at Newnham. She was very vocal about issues at school, too, and would write about it to her family and sometimes criticisms to the school about their teaching. She was also unhappy about how the war was impacting her school, which she complained about in letters home. She wrote to her family about her complaints, politics, her schooling, exams, and interesting occurrences in day-to-day life. During war-time she would write about air-raids and other war-related events that were happening around her.

WWII started during Franklin's second year at Cambridge. Her father believed that she should be doing something more for the war effort, while Franklin believed she would do the most good to continue to pursue her degree in chemistry. "As my father saw it, Rosalind was taking an unwarranted soft option," Franklin's sister writes in her memoir My Sister Rosalind Franklin, "this was the time when my mother … firmly took Rosalind's side, convinced that she was right to stay in Newnham. Rosalind was, as she herself explained to my father, anxious to do some sort of war work in the vacations, helping my parents with their work for refugees, and was anxious, too, to have some sort of war work using her scientific skills when she graduated--it was then, after all, 1941, and the country was still in crisis. By the time the war was over, the direction of Rosalind's life was clear." She was introduced to x-ray crystallography in college. I was very fortunate to find some of her notes from her college classes.*

She did very well in school, however, she was always very nervous about exams. She often performed very well, though. She wrote many letters home about her anxiety about her exams in college. Franklin went on to get a degree in physical chemistry. In 1942, she left college and began her work with coal. *Note: After writing this I came across even more of her notebooks from school which are published in an online collection of her papers here: wellcomecollection.org/works/h4yftrdd

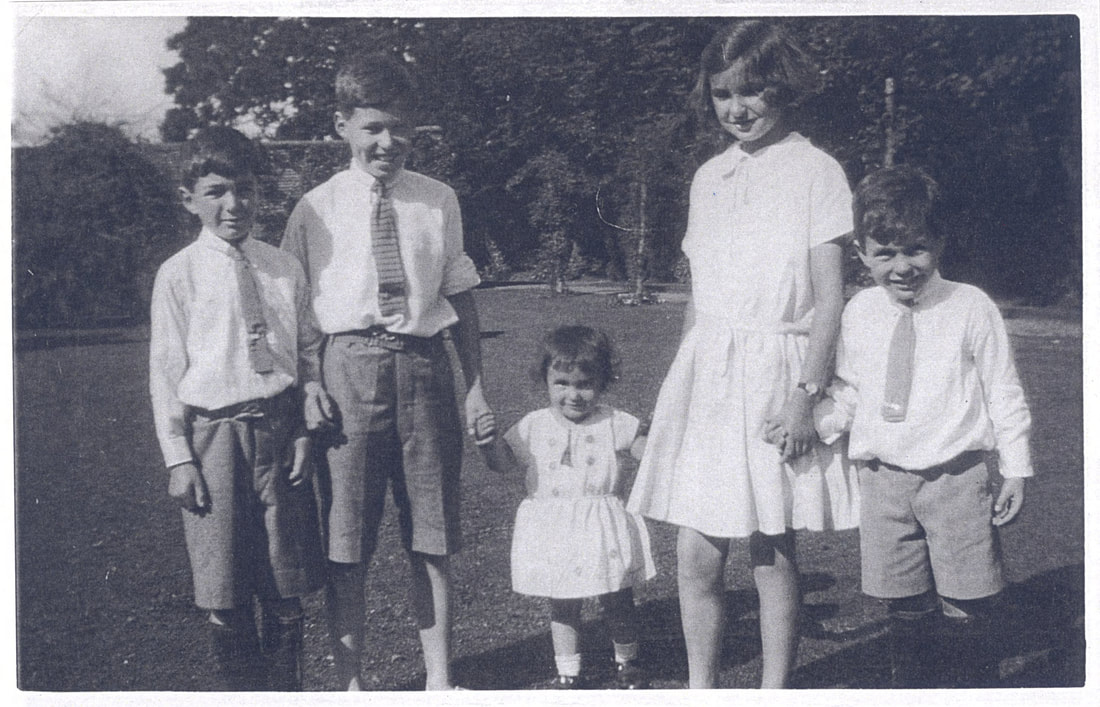

Rosalind Franklin was born on July 25, 1920, in Chepstow Villas in Notting Hill, London to Ellis and Muriel Franklin. The Franklins were a prominent Anglo-Jewish family in Notting Hill. They had five kids, Rosalind Franklin being the second oldest of them.

She was fascinated by science at a young age. Her brother Colin describes how she loved printing photographs with her mother: "Developing and printing photographs at home, with my mother, was a discovery which thrilled her in childhood, swilling the sensitised paper in a tray of water... watching the image appear, removing it at the right moment of development. I remember her exclamation which pleased my mother, 'It makes me feel all squidgy inside.'" She began attending St. Paul's Girls' School at age 11 in 1931. She was already showing signs of her interest in science at that age. Her sister described that "early traces of a careful and excited scientist had already appeared [in Franklin].... Indeed, many traits of her character were already clear -- her intelligence, her skill with her hands, her perfectionism, her logical mind, her outspoken honesty." Her mother also said: "All her life, Rosalind knew exactly where she was going, and at sixteen, she took science for her subject." Franklin did very well in school. As her sister says, "Rosalind's school certificate, in spite of the usual exam nerves, brought her six distinctions, an easy overkill for a matric. For she was able at all subjects, and particularly interested in history, though she never doubted that specialization meant science. And it was to be physical sciences and maths, not biology or botany which were mainly for those wanting to be doctors." She decided to go to Newnham College at Cambridge University. Newnham was one of the two women's colleges at Cambridge University, the other being Girton. She chose Cambridge because, as her sister puts it: "Cambridge, it was assumed, was the best place for science." And in 1938, a year early, she headed off to Cambridge.

She didn't just do work in DNA. She made great contributions to other studies. She did research involving the micro-structures of coal before she worked on DNA. After her work with DNA, she changed to studying plant viruses. In this blog, I will tell her story. I'll start with her childhood and tell the story of her life up until her untimely death. I'll also explain the chemistry behind her work. Read more to learn about this amazing scientist and what she's done for the world.

|

AuthorLoren Sinclair is a high school student interested in chemistry, art, computer science, theater, and everything else! They are writing this blog to tell Rosalind Franklin's often untold tale, from her life story to the science behind her work. Archives

January 2022

CategoriesSources |